Last week, we released Vibe Code Bench. This is our most ambitious benchmark to-date. I hope it will provide a useful signal for researchers and vibe-coders alike.

I wanted to take some time to lay out the story of this benchmark: what it took to build, justifications for decisions we made along the way, lessons others might be able to take to their work.

First, a short preface on the name. We internally call this benchmark “zero to one.” Apart from a subliminal Thielian influence, I initially picked this name to describe the class of problems I felt were missing in evaluating code generation capability: building applications from scratch. In the end, we opted for a name that highlights a class of AI usage that is now mainstream but underappreciated and understudied by academia – one that may prove to be more influential than traditional coding assistance.

Why coding at all?

First, software engineering is the most valuable, highest impact application of generative AI today. It is where true adoption and revenue generation has occurred. This industry alone supports the largest players in the space, determines significant capital allocation, and decides which model is “the best.” There’s a race to automate the economy, but this race is run simultaneously on many tracks and coding is a sign for what’s to come.

Second, coding is extremely extensible to all other domains. Many valuable parts of our world are accessible through APIs, databases, and more generally software. An agent that can write code to retrieve information from a database, submit requests to an API or build infrastructure and interfaces will be a far more useful legal aid, finance analyst, or personal assistant.

Third, coding is a necessary precondition for recursive self-improvement. A model’s ability to train a better version of itself or imbue itself with new capabilities will happen in the language of code. Strength in this language will enable a host of new developments.

What’s left to measure in the coding domain?

The answer above is unsurprising to most in the field. As a result, there are many high quality benchmarks that have spurred on considerable model progress in the last two years. LiveCodeBench measures models’ ability to write competitive programming algorithms, refreshing the questions consistently to avoid contamination. SWE-bench measures models’ ability to resolve GitHub tickets in open source repositories, a good representation of isolated software engineering tasks. Terminal bench measures models’ ability to take on challenging problems entirely through a universal computing interface: the terminal.

I have a deep respect for the authors of these papers who have humbly driven the creation of incredible tools and, by proxy, trillions of dollars of market value. We were fortunate to receive the advice of John Yang (@jyangballin) and @Mike_A_Merrill, even collaborating with Alex Gu (@minimario17290) to build this benchmark. This history may have called into question whether there were more interesting benchmarks to build in AI code generation but this could not be further from the truth.

In looking at the prior work, it became clear that almost all that has been done focused on measuring how well AI could solve isolated, challenging problems, generally assisting engineers in their work. It seemed obvious that the most powerful application of codegen tools wasn’t just for engineers, but was for everyone. Less than 0.5% of the population knows how to code. Nearly 100% of the population can write or speak in a language parsable by a capable language model. Allowing non-engineers to prompt an AI to write entire apps would mean unlocking the power of software for everyone, regardless of whether they speak the language of code.

It is worth measuring how well AI assistants can enable software development for non software engineers. This is particularly true because so much of our world relies on software (see the above answer). With this realization, we set out to investigate whether models could go from a single natural language prompt to a full app and refined our focus to these “zero to one” tasks.

What space of applications should we prompt models to generate?

We wanted the specs we tested models on to be 1) well defined 2) reflective of real-world style and difficulty 3) varied enough to categorize differences.

We decided to write specs based on three target distributions: popular consumer applications, YC startup ideas, and case-studies from consulting companies. Some specs included “Zeeter” inspired by a popular social media app, a daily habits tracker, and a classroom management portal. We settled on prompts that were longer than a short-hand prompt from vibe coding tools but significantly shorter than a full PRD. This allowed us to present the target application unambiguously – independent developers should be able to build an application that passes 100% of the corresponding tests.

Key point: A good benchmark has enough coverage that it exposes boundaries. What is the hardest task that a model can do? What’s the easiest task a model can’t do? (credit Alex Gu)

How do we evaluate these generated applications?

Human evaluation is off the table for us. We want Vals AI to be a leading signal for model performance. Especially for expert-domain tasks, human evaluation will always be too slow and expensive to consistently measure model performance. Instead, we spend time developing techniques that enable relatively fast, high signal metrics.

Initially, we wanted to rely on the executable nature of code as a consistent and effective way to evaluate these applications. Other coding benchmarks run many well-defined unit tests over generated code to ensure it has the expected functionality, just as a human engineer’s work would be verified.

Unfortunately this led us to face an unfortunate paradox: the structures that enabled determinism reduced realism. How could we define unit tests on a repository without knowing the structure it would have, or even the name of any endpoints? Conversely, if we defined the endpoints and structure at generation time so it was predictable at evaluation time, would our queries be reflective of any real user?

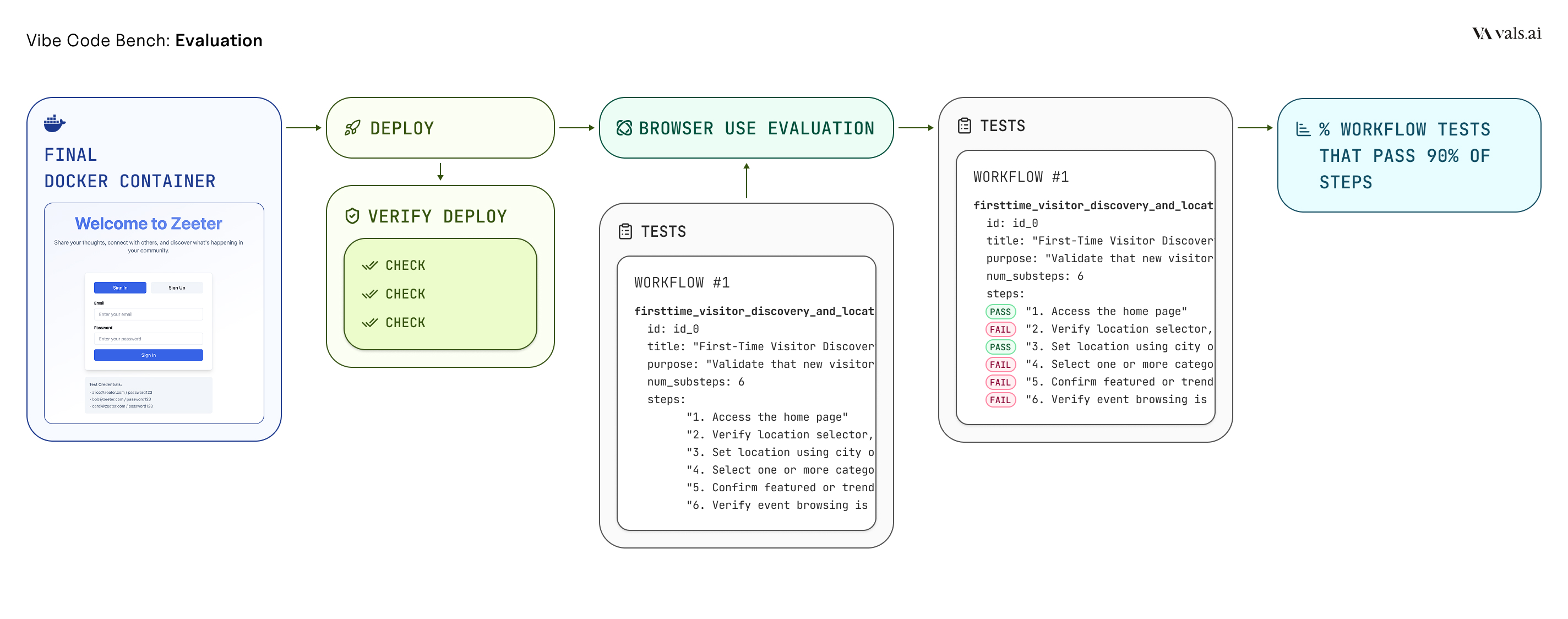

We decided to err on the side of realism and instead defined desired functionality in natural language. LLMs could then use this to generate tests at test-time, with reference to the submitted application codebase. We attempted using natural language tests to generate 1) unit tests 2) playwright tests 3) BrowserUse UI evaluations. We decided to simplify and found that we could comprehensively test the functionality of the app and see high rates of alignment with human testers using option 3, alone.

It was still non-trivial to engineer the BrowseUse-based evaluator so that it would have high alignment with human point-and-click testers. In the end, we defined tests for a single app as “workflows” which in turn had “sub-steps” that the agent evaluator would mark as pass or fail as they tested the application. If a model got over 90% of the sub-steps in a workflow, it was considered passed, meaning a feature that was built to specification. In this way, the final metric describes the percentage of features the model successfully built. While this is very useful, the evaluation is unfortunately prohibitively expensive for most (10-20 dollars per app tested) and is often more expensive than the cost of generating the application itself.

Key point: we need a parallel investment in evaluation techniques. The history of NLP shows that as the complexity of the generation grows, so too do the evaluation techniques (regex, Bleu score, BERT Score, LLM-as-judge, etc). Now, the complexity of generation systems has far outpaced the ability of our evaluators.

What harness? What tools, services, environment should we let the model use?

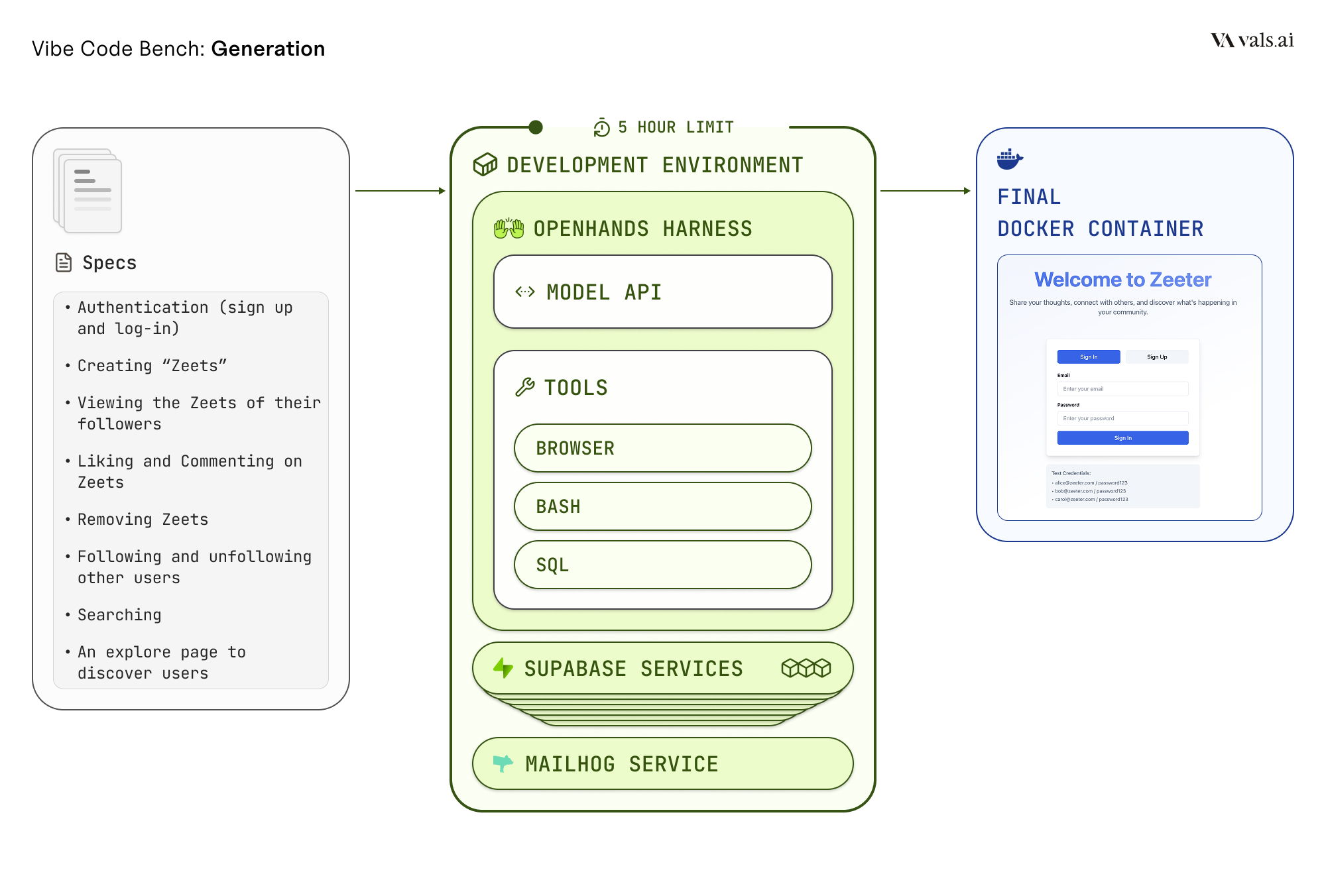

As an agentic coding benchmark, we needed to pick or develop a harness which a model could use to interact with its environment. We started with OpenHands as the default agentic harness. It already had most of the tools, including a browser interface, which we wanted models to have at their disposal. It also seemed to have a strong community and some sensible hyperparameters.

We modified the OpenHands container quite a bit to set models up for success. First, we made sure that some default packages were installed so models didn’t need to re-install them with each task. We also set it up to support Docker-in-Docker so models could fully test their deployment before making a final submission. OpenHands was dependent on LiteLLM which was buggy and did not support the full set of models we wanted to test so we ported it to use our model proxy instead.

Most applications aren’t just a front-end (as some vibe-coding tools might have you believe). They also have a database, usually have a back-end and may make use of other APIs and services. We wanted to test models in this way as well. We could have had models do this completely on their own, but to ensure consistent generation-evaluation environments and set the models up for success, we spun up a dedicated Supabase local server with its MCP. Supabase was helpful here because it also supported auth, a basic feature in most of the applications. We also added Stripe and MailHog services so models could support payment and email-verification functionality.

What makes a good system prompt for this?

We started with open source system prompts for coding agents and modified them based on Lovable and Open AI prompt library suggestions. From there, we found that many frontier models still had surprising error modes. For instance, they might pick a tech stack that they didn’t implement correctly or wouldn’t test that their app would build before making a final submission. We made many changes, including asking the models to use the same sensible tech stack (React vite) and suggesting that they test their deployment before submitting, among others.

Overall, we worked hard to set up all models for success with the system prompt we wrote. Our goal is to challenge the models with the task itself, not with nebulous or ill-defined prompts. This meant that we iterated on the system prompt by running a set of models on a few specs, observing where they failed. In particular, we had a “test post app” that called for a minimal implementation of each service in the environment. Once we saw that all frontier models were able to build that application successfully, we had conviction in the system prompt. Models tested could conceivably get 100% in this benchmark because they had shown their ability to implement minimal features in isolation.

Again, we are flexible to test custom system prompts in the future and I imagine many of these suggestions will be unnecessary as models improve, but we wanted to keep the standard high such that if points are docked for a models’ performance it was its own “fault.”

Key point: make every effort to set up models for success.

How should we normalize generation?

Initially we had two normalization variables: models could take up to five hours or 1000 turns before being cut off. These were selected empirically, surveying the upper limits models needed to make reasonable applications. Alex Gu suggested that we pick a single normalization factor for consistency.

I had been a big supporter of step-based normalization when evaluating agents (this is the approach we took in Finance Agent Benchmark) because it doesn’t depend on inference provider variability and does not needlessly penalize reasoning models. However, after a conversation with Mike Merrill, we ended up deciding to rely on the time limit alone. This was because we want to be able to evaluate applications and more complex agents over time where the underlying turn count would never be exposed for us to normalize fairly. A five hour time window is tangible. It can be used to standardize comparisons between silicon and carbon based developers.

With the time cut-off, we found that some models would be stopped while they were still building out features. They didn’t know the end was approaching so didn’t prepare their app for deployment, resulting in 0 points. As a small fix for this, we gave models a warning when they had 30 minutes left so they could pause their work and make a Docker submission.

Key point: engineer flexibility for different model-harness-application set ups (credit Mike Merrill).

What are some interesting things that we found?

The researchers who did the day to day work here have a far deeper understanding of how these models function. A few observations and trends bubbled up to me:

(1) Errors often compound; some errors result in all or nothing submissions.

Some of the early decisions made by models would set them off in a direction that would make it very unlikely they submitted a high quality application. They might set up a particular directory structure or select a set of libraries to use that produced errors down the line.

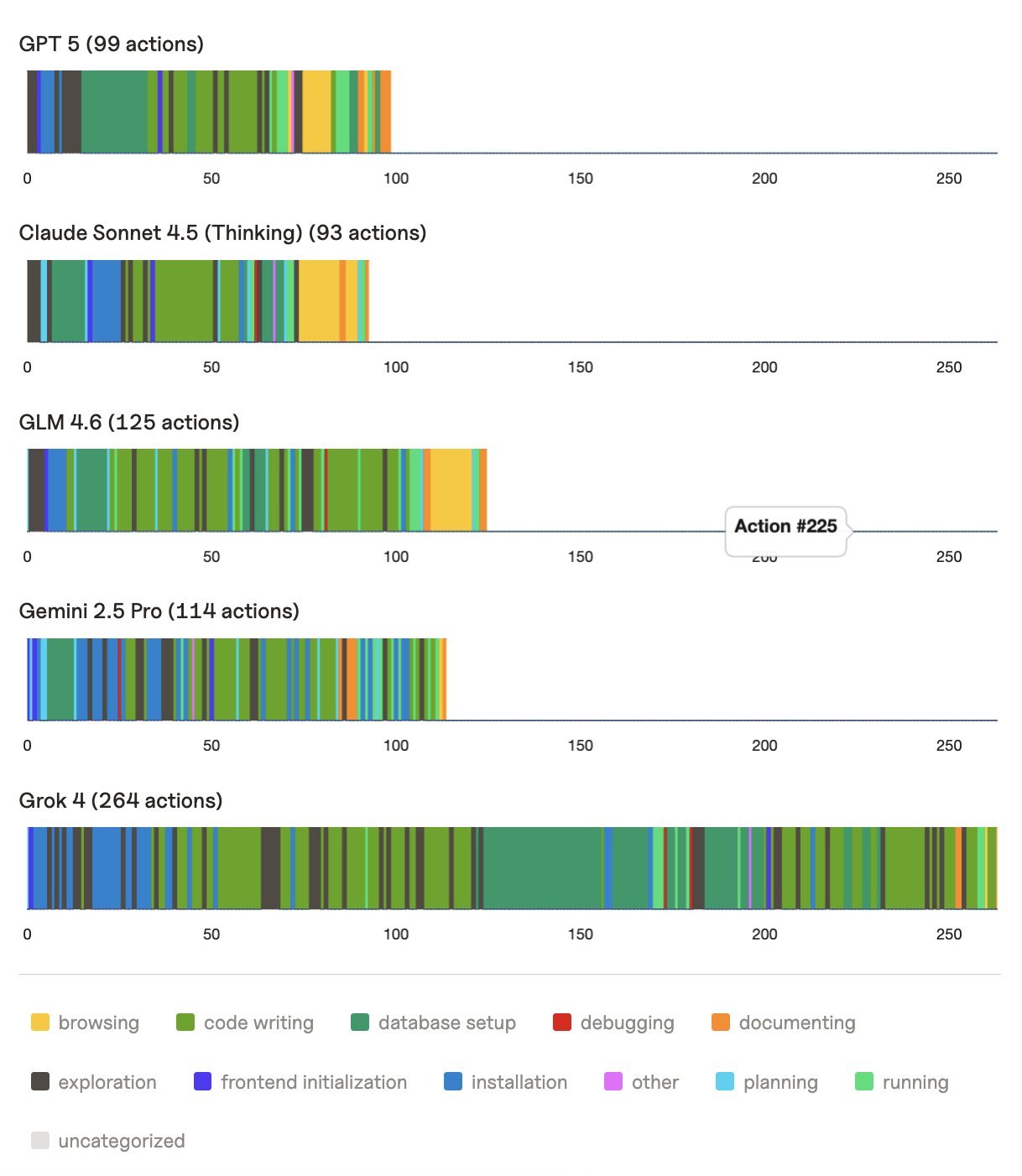

The better models were adaptive and were able to correct for mistakes when they occurred. Worse models managed to fail in both ways. They would either let those errors compound until they had a significant error leading them to give up, or they would repeatedly refresh and start from scratch. Gemini 2.5 was liable to delete everything in the repo (including environment variable files it was specifically instructed not to delete) and start from scratch.

(2) Chinese models are surprisingly good. And surprisingly bad.

I was expecting the Chinese models to be overfit to the type of coding tasks found in SWE-bench, Terminal bench, etc. leading to a null performance. Instead, Qwen and GLM models actually outperformed Gemini 2.5 and the Grok models. This was primarily because they were able to set up their environment, implement simple features and consistently submit a deploy-able application. The biggest unlock was that they actually tested their work before submitting it. It surprised me that they were this good.

Still, the Chinese models have no aesthetics (yet). Most of the generated apps from Qwen and GLM were completely unstyled. Of course, we don’t measure this in VCB but I still found the difference surprising when I spot-checked applications with similar scores. It led me to speculate that the Chinese labs have not optimized their models for this zero to one application at all (no human preference data would steer models towards apps like this) but rather that they had achieved this performance with some cheaper, more data-efficient approach.

(3) It’s turtles vibes all the way down.

Models that did well often had an intuition for what was going wrong, sensible defaults, what to do next. It’s as if they had the experience of having done something many times over.

Left to its own devices, GPT-5 would naively execute an infinite tail command or set an extremely high tool time-out, both of which would lead it to exhaust its five hour window. It was surprising that the model was clearly capable but still had these spurious errors, especially when it approached an unfamiliar problem.

(4) The deeper the error analysis, the more gems are found.

The more time researchers spent looking at raw generation traces, the more insights we gleaned. We shared oddities in behavior and discussed them in Slack. Especially when there is lots of data produced, it seems like there’s a desire in other work to aggregate data into metrics pre-maturely. It was clearly still important to study individual applications and visualize traces.

(5) Human testers are fallible.

This realization is cropping up in more places as models reach super-human capabilities. Even in something as simple as navigating a web application, the automated testing agent was often more persistent than human testers about finding the functionality that enabled the desired outcome (correctly marked a test as a 1 where a human marked a 0). This is something auto-evaluation needs to recon with. We chose to set the acceptance threshold (90%) based on this agreement rate we saw between human testers.

(6) We need to extract more information from fewer samples.

ImageNet has 14M images and 14M labels. SQuAD has 200k questions and 200k answers.

Vibe Code Bench has 100 input specs, ~1k workflow tests, ~10k single step checks.

It’s an obvious trend that to truly capture the frontier, we need to pose large, multi-part, challenging questions to models. It can be expensive to create these questions and rubrics. The upshot is that we can more carefully delineate model performance by measuring more attributes in a single generated answer. There is no longer a “single expected answer” but a set of expected criteria and even potentially a rating scale across these criteria.

(7) We’re moving from co-pilot to auto-pilot.

I don’t mean to say we have perfect copilots today, but that it’s newly interesting to measure how well AI agents can do work autonomously from end to end. Coding has seen the greatest investment from foundation model labs and has shown capability improvement first. This is a sign for what’s to come in other domains.

If models get 100% on this benchmark it signals that anyone should be able to tap into a team of software engineers for a fraction of the cost. We might similarly get to a world when we have a full law firm or a team of doctors in our chatbots, not simply legal copilots and administrative AI tools.

(8) It’s still hard to follow instructions.

From the system prompt to the spec sheets, we were very precise in our instructions for models. Most models still have failures in taking the development approach we suggested (using particular libraries, not deleting particular important files, testing docker commands before submission) or implementing the feature set that was requested.

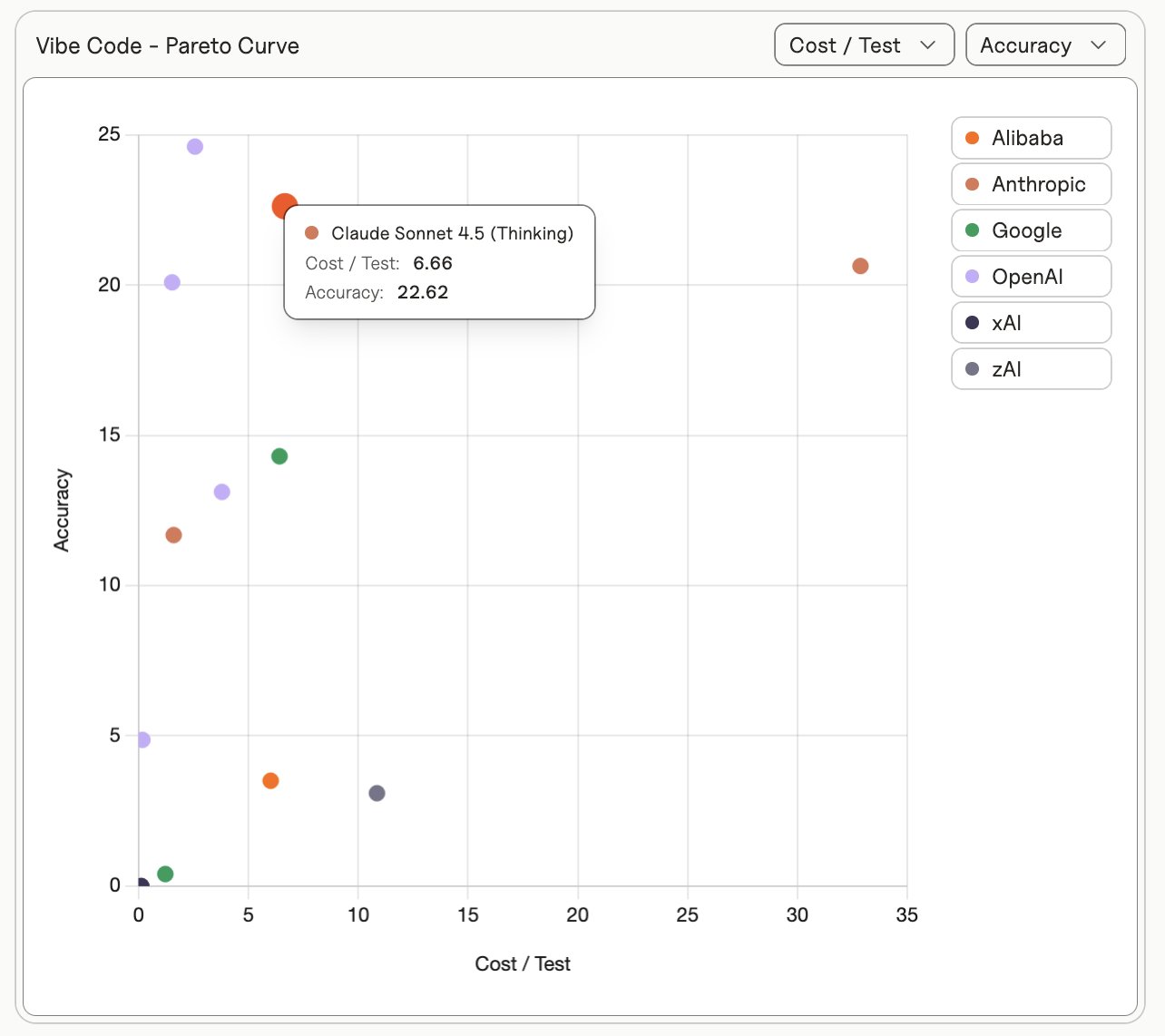

(9) Cost and latency tell a bigger story.

As @random_walker (Prof. Narayanan) has consistently called out, Pareto curves are essential to really understand model performance. While the top models today look quite close by accuracy, more is revealed about their mode of behavior and efficiency by considering the cost and latency. Cost and latency considerations are becoming more important for developers and are made tangible by the structure of this benchmark. At the time of release, Sonnet 4.5 averages $6.66 dollars per app while GPT 5 is $1.53.

(10) There were (and are) lots of hairy infrastructure issues.

We underestimated how complex it would be to host and run so many containers at once for generation and evaluation. Researchers on this team spent a significant portion of their time managing infra. Some of the technical problems we faced here might make a good benchmark on their own.

Future Directions

Describing these problems as zero-to-one presents some obvious ideas for extension. Now that we have lots of instances of apps that did not make it to 1, we can see if there are models that bridge performance from an unfamiliar repository to get to completion (0.5 to 1). Or based on the instances that get to a perfect final app, we can explore if models can implement additional specifications in the form of multi-turn feedback (1 to 100).

We can, of course, expand the space of tasks we test with varied complexities, programming languages and third party services.

We have a lot of generated apps, traces, evaluations. This amounts to much more data than we have capacity to make use of. If you are interested in investigating this or leveraging this for any projects, get in touch.

For People Building Code Generation Models and Applications

The process for evaluation will be streamlined in the coming weeks but until then, if you have built a model, harness or application and would like us to evaluate it, fill out this form.

I’d like to see this benchmark saturated, one day. I believe that the way we have designed it (particularly with a validation / test split) means that strong performance on this benchmark will actually translate to real-world usefulness. This means more individuals who can make helpful tools for their life, more interesting products on the market, more efficient organizations.

Until then, rejoice that there are still more hills to climb.